- Home

- Amrinder Bajaj

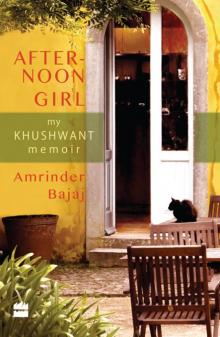

The Afternoon Girl

The Afternoon Girl Read online

Afternoon

Girl

My Khushwant Memoir

AMRINDER BAJAJ

O Nature’s noblest gift, my grey goose quill

Slave of my thoughts, obedient to my will

Torn from the parent bird to form a pen

The mighty instrument of little men.

Lord Byron

for

Mamaji

without whom this would not have been possible

KHUSHWANT SINGH

The trinity he worships is

Booze, big bums and bad jokes

Though,

He wouldn’t like to own it now.

He cares not for religion and yet,

Translates holy texts into English.

A lovable paradox, a nasty old man,

A rip roaring raconteur, a stuffed shirt,

A stickler for time, abrupt and rude.

A charmer, a brown gentleman who

Calls English his mother tongue.

A connoisseur of beauty – in women,

Who hover around him

Like butterflies on nectar.

He has no patience with god-men

And soothsayers, though

An occasional comely

Sanyasin holds his interest.

There are myriad facets to his

Kaleidoscopic persona

Of which,

I have glimpsed but a few.

Many have capitalized on his name,

Many, like me, ride on his shoulders

The road to fame.

What he writes sells,

What is written about him sells.

Though he has mastered the

‘Art of bullshitting’

The public scoops up handfuls,

Like the dung of the sacred cow.

Till they invent

A ‘condom for the pen’

He will write and regale

Till he drops dead.

Three cheers for the grand old man

Of Indian literature and his

Deceptive aura

Of a dirty old fellow.

Contents

Epigraph

Dedication

Introductory poem

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

1

What does one write about a life as transparent as Khushwant Singh’s? There is not much that is not known – his wisecracks, his penchant for women and whisky, his prolific writing and the intellect that shines like the sun through the cloud of the badly dyed, badly tied grey beard.

Each time I met him – invariably in the afternoon, for that was the only time I could spare from my medical practice – I found him ensconced in a chair facing the door, his feet propped on a mooda that lay sideways in front of him. It was as if he never got up in between visits. The phone, pens and the lined yellow sheets of paper lay as if forever on the table to his right. The only unpredictable thing about him was his mood and the turn our conversation would take. If I was welcomed as a long-lost friend during one visit, I would be ticked off and put in place during another.

I had learned early in our association that one had to take a prior appointment – as the intimidating notice on his door stated, though he was considerate enough to take into account my timetable before fixing the date and time – a commendable trait in a man of his stature. He did not take kindly to anyone being late. Raised in the armed forces, I was punctual by default, but there were matters beyond my control that led to occasional delay – like the time there was a diversion of traffic during the rehearsal of the Republic Day parade and I had to make a wide detour. Terrified of the scolding I received that day, I reached Sujan Singh Park fifteen minutes early for my next meeting. I dared not find out if reaching early was as much a breach of protocol as reaching late; so I spent an excruciating quarter of an hour outside his window in the furnace of my old Fiat under a merciless June sun.

Over the years, I metamorphosed from the pest he tolerated on account of my mama (who was his family physician and cousin’s husband) to a welcome visitor. Though I reached a point where I had no qualms about cracking bawdy jokes with him, I remained ever in awe of his persona – a paradox difficult to explain.

Initially, it was to kick-start my writing career that I sought an audience with him. I had won poetry-writing competitions in school and college, my short stories in the college magazine were widely appreciated, and I had begun to believe that I had it in me to become a famous author. But life forced me to downgrade my opinion of myself, for the masterpieces that emerged from the depths of my soul had no takers. Disheartened by the pile of rejection slips, I yearned for a mentor. And my thoughts turned towards Khushwant Singh, the only man of words I could approach.

He was a journalist, novelist and a columnist of no mean acclaim. He spoke his mind fearlessly and was read widely. In fact my first ‘adult’ book was his Train to Pakistan, which I still consider his best.

The first time I met him was at Mamaji’s place long ago. Having returned from a game of tennis, he was in a T-shirt and shorts. A burly Sikh with a luxuriant black beard and a well-toned body, he exuded the kind of virility from which I, a shy young virgin, shrank involuntarily. There were hush-hush stories of him being a womanizer and that he liked his women heavy-bottomed and bosomed, a notion that gained him instant notoriety, though he was to spend the rest of his life negating such insinuations.

Later, when I was in my mid-thirties (he was thirty-five years my senior), I asked Mamaji to arrange an interview with him. I knocked on his door at the appointed hour with much trepidation. The Khushwant Singh I now saw was a shrivelled caricature of his former self. The unnaturally black beard was sparse and untidy as a crow’s nest and badly needed a repeat dyeing as the white showed at the roots. He sat on an armchair facing the door with his feet up on a transverse mooda. The room was stark, with none of the expensive artefacts that one expected in the house of the rich. I saw not the quiet elegance of old money but a comfortable, lived-in place with

plenty of bookshelves. There was a fireplace to his left and a low centre table stood on the bare floor. Photographs of family and friends occupied a shelf by the window and an occasional painting on the wall completed the layout of the room. Over time, as the man and his home grew on me, I realized that it was the very simplicity of the environs that set him off to perfection.

He made no effort to get up to meet a mere supplicant, though she was a lady. I sat uneasily on the edge of the chair to his right and was offered tea and toast. Little did I know that it was a rare honour, for I barely tasted another morsel at his home. He was not the average Indian host who stuffed you with snacks at any time of the day, but a brown sahib who shared with you what he ate and, more importantly, when he ate it.

Bearing his reputation in mind, I had brought a couple of short stories for his appraisal. There was one with dirty words (for I thought that was what he would like), about a childless industrialist who arranges the dowryless wedding of his idiot brother with the daughter of a poor man so that he could impregnate her and ‘adopt’ his own son; but the mousy woman shows rare spirit and defeats him in his game. The second was a sensitive tale about a beggar boy whom I had befriended at a red light crossing. Though I never gave him alms, a strange affinity developed between us. Perversely, when he stopped pestering me, I surprised him with a fifty-rupee note. With a whoop of delight, he sped across the road to tell his friends about his windfall when a speeding truck crushed him to death. The last part, of course, was made up.

Handing Khushwant Singh the short stories, I told him that I had also brought along a few poems for his appraisal. He refused to consider them, saying that poetry does not sell. I returned after a few days, eager for his opinion. He was patient and kind, asked me not to use clichés and said that the essence of a good story was understatement, illustrating his words with short stories by famous writers.

I was a good pupil and learnt quickly. I wrote a story titled ‘The Scavengers’ and sent it off to him. To my delight, Khushwant Singh approved of it and sent me a note:

3.4.86

Dear Dr Bajaj

I thought that the best way to handle your story was to rewrite it in this way. Have it re-typed (duplicate) after you have gone over my version and made whatever changes you would like to make. I think the title ‘The Way the World Goes’ is less obvious than ‘The Scavengers’. You can try the story on any magazine you like. I will be happy to take it for the Telegraph for which I select stories. Do let me know.

Yours

Khushwant Singh

N.B.: It’s best to use your full name and omit ‘doctor’.

Thus that story and, later, the one about the beggar boy found their way into the Telegraph and I received a princely sum of Rs 150 for each. The thousands I earned as a doctor did not give me as much pleasure as this paltry sum.

2

Our association has been captured in letters exchanged over a period of twenty-five years, for I have preserved every word I received from Khushwant Singh, even if it be a derogatory one-liner. In moments of solitude, they ignite memories that lie heaped like autumn leaves in the forgotten recesses of my mind. What prompted me to put our correspondence on paper was the biography of Charlotte Bronte by Lyndall Gordon. At the cost of sounding presumptive, I was struck by the uncanny resemblance in the thought process of women writers born more than a century apart. It was as if I had met my soulmate in an encounter that defied time and space.

Victorian England and present-day India seemed similar in more ways than one. Charlotte’s rebellion against norms that straitjacketed womanhood struck a chord with me. Moreover, her struggles as a writer made me take heart. She was in her thirties when she lamented to a friend that she had done nothing of import yet and life was slipping by. She feared that the pressure of earning her living would lead her to lose one faculty after the other till nothing was left. The pressure of raising a young family and tending to an exacting profession left little time for my passion as well; and, having achieved nothing worth mentioning so far, I too was in a state of panic.

It was heartening to learn that she too relied heavily on autobiographical experiences. It dawned on me much later that all fiction grows from a grain of truth.

Charlotte decided at the age of twelve that she would never marry and would dedicate her life to writing instead. At that early age, she preserved her writings in hand-sewn ‘books’ with professional layouts, including title and contents. I too wrote juvenile poetry in a similar format around the same age. Like her, I decided not to marry, though I vacillated between devoting my life to writing and medicine, influenced as I was by Florence Nightingale as well. Marriage and a family, I knew, would not allow complete dedication to my calling. I had not reckoned with a dominant mother who forced an arranged marriage upon me and harnessed me to domesticity.

During her struggle to be recognized as a writer, Charlotte longed for a literary father but was rebuffed by such celebrities as Robert Southey, just the way I was by Khushwant Singh at one point. One may think that it is indeed bold of me to compare myself with the legendary writer, but I am speaking of that time in Charlotte’s life when she was a mere village woman as desperate for recognition as a writer as I am today.

I could identify with her dependence on Monsieur Heger – her teacher at the Pensionnat at Brussels, a relationship that was neither sexual nor platonic but as important as life itself – for such was my attachment with Khushwant Singh. If it was love that she felt for Heger – and I felt for Khushwant Singh – it was beyond the realms of love as it is commonly understood. Like her, I felt that ‘his mind was my library, and whenever it was opened to me, I entered bliss’.

Heger was a ‘little black ugly thing’; neither did Khushwant Singh have the looks that could entice a woman. It was the power of the mind that attracted us to our respective objects of devotion and made us respond to them in a way it was impossible to respond to anyone ever after. She cried her heart out unable to take his rebukes even as I did on account of Khushwant Singh, for I was keenly sensitive to his responses or the lack of them. Brushing aside all sense of decorum, I laid bare my heart. I got no confidences in return, no solutions to my problems, no introductions to people in the publishing world, and yet I went to him again and again, despite myself. I lived from one meeting to the next, prettied myself as I would for a lover and yet did not crave physical attention. In fact I would have taken flight had he made an overt sexual gesture. The palpitations were due to apprehension, the flush on my cheek due to excitement, the light in my eyes due to intellectual stimulation and the non-stop jabbering due to nervousness. He had the knack of drawing me out and was a good listener.

As Heger told Charlotte Bronte to ‘sacrifice without pity, everything that does not contribute to clarity’, Khushwant Singh told me to prune my work heavily, adding that the first draft of a novel even by the most eminent of writers was unreadable. One has to go over the manuscript again and again to bring it to a printable state. The one thing that measures a writer’s talent is recognition and as that eluded me, I paid heed to Khushwant Singh’s words.

M. Heger had told Charlotte that ‘genius without study, without art, without knowledge of what has been done, is strength without lever. It is the soul that is within but cannot express its interior song save in rough and raucous voice.’

Khushwant Singh too encouraged me to read the works of geniuses and learn from them when I believed that my ‘unique’ style should not be influenced by the work of others, however great.

Charlotte expressed her potential in a thinly veiled account of a painter who arrives in a foreign land with nothing to recommend him but his faith in his own genius. In a letter soliciting the patronage of the lord of that country, he states: ‘Milord I believe I have genius. Do not … accuse me of conceit; I do not know that feeble feeling …

‘Throughout my early youth, the difference that existed between myself and most people around me was for me an embarrassing enigma that

I did not know how to resolve. I believed it my duty to follow the example set by the majority … an example sanctioned by the approbation of legitimate and prudent mediocrity, yet all the while I felt myself incapable of feeling and acting as they felt and acted. In what I did there was always excess; I was either too wrought up or too cast down, I showed everything that passed through my heart and sometimes storms were passing through it.

‘Milord, it is to put myself in a position to exercise that faculty that I entreat your help … I know that in the long run, true merit always triumphs, but if power does not offer a helping hand, the day of success can be a long time in coming. Sometimes indeed death precedes victory.’

It took Charlotte Bronte enormous daring to bare her indomitable conviction of her potential greatness and invite her teacher to promote it. M. Heger, usually profuse in his response, refrained from comment and made mere grammatical corrections on the margins. Similarly, I had once written to Khushwant Singh that I was a peepal sapling that had germinated in the crevice of a concrete wall. If only he would replant my talent in fertile soil, I could grow to my full potential! He too chose to ignore my poignant appeal.

I strove to pursue my passion within the constricting confines of matrimony. My father told me to persevere, for water always finds its level. How could I explain to him that I was a sports car stranded behind a bullock cart on a one-way Delhi road? I needed a free highway to drive full throttle.

Though M. Heger ignited the passions of his female pupils through intimate looks and provocative statements, he withdrew when it impinged on his domestic life. When Charlotte left the Pensionnat on account of his suspicious wife, who saw more in their relationship than they cared to admit, she subsisted on the letters they exchanged. She’d tell Monsieur Heger time and again that the letters were her life. The fortnightly exchange of epistles was drastically cut down to a letter in six months by the wife, who once pieced together the fragments of a letter from her husband’s dustbin and did not like what she read. Day after day, Charlotte waited for the post as one waits for vital sustenance. As his correspondence became scantier, she disobeyed the restriction imposed and begged him to write even if to reprimand her. All she craved was a letter – a crumb from a rich man’s table; but his silence continued interminably.

The Afternoon Girl

The Afternoon Girl